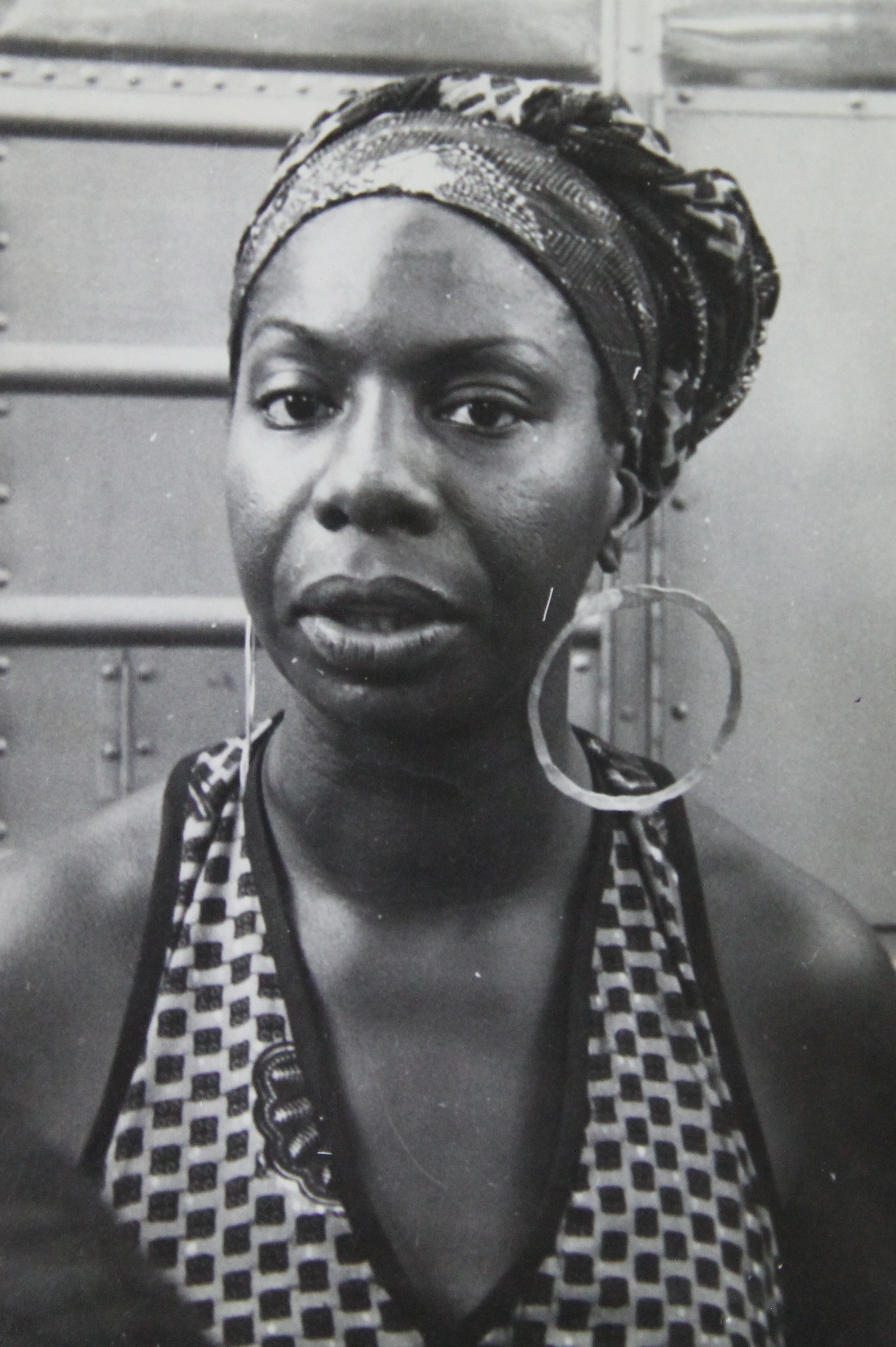

Photo of Nina Simone. Photo Credit: Gerrit de Bruin, courtesy of Re-Emerging Films.

80 Years of Protest Songs Part 1: 1939-1958

80 Years of Protest Songs Part 3: 1979-1998

80 Years of Protest Songs Part 4: 1999-2018

The 1960s ushered in what is often considered the golden age of protest tunes. Civil rights and the Vietnam War were hot button topics. Many of these issues spilled over into the 70s. Along with folk and soul, punk started to emerge as the voice for disfranchised youth. On the world scene reggae, afrobeats, and other musical genres were used to express discontent in their countries.

We Will All Go Together When We Go – Tom Lehrer (1959)

Lehrer was a satirist and mathematician who often employed biting humor to provide social commentary. On “We Will All Go Together When We Go,” he discusses the threat of nuclear annihilation. He also explores the subject of race relations and class distinctions by establishing death as the great equalizer.

Tears for Johannesburg – Max Roach (1960)

This tune is the closing track off of Roach’s 1960 album, We Insist! Max Roach Freedom Now Suite. I was tempted to include the entire album because all five tracks link closely together to make a powerful and cohesive 37-minute whole. The influential jazz composer and drummer was one of the few jazz musicians to release an entire album of overtly political material. Because of this, at the time the album was considered polarizing and controversial. In retrospect it is now considered a landmark album.

“Tears for Johannesburg,” links the civil rights struggles in the US with the struggles taking place during South Africa apartheid.

Where Have All The Flowers Gone? – The Kingston Trio (1961)

Pete Seeger wrote the melody and the first three verses in 1955. Joe Hickerson penned additional verses in 1960. The Kingston Trio had a chart hit in 1961. The song provides poignant anti-war commentary by raising a series of pertinent questions. One question which still resonates is “When will we ever learn?” It highlights human’s sad inability to learn from history.

The Ballad of Ira Hayes – Peter Lafarge (1962)

Ira Hayes was a Native American of the Pima Tribe, who was also one of six marines who raised the flag at the World War II battle of Iwo Jima. Once he returned home, instead of being treated as a war hero he was a victim of prejudice and “the white man’s greed.”

Peter Lafarge’s father was a notable anthropologist who heavily studied Native American history and culture. This interest rubbed off on Peter who wrote several songs about the Native American experience.

A notable version of “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” was recorded by Johnny Cash and appeared on Cash’s 1964 album, Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. Cash also covered four other Lafarge songs for that album.

A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall – Bob Dylan (1963)

Bob Dylan composed many songs which became an essential part of the cannon of protest songs. This tune may be his most epic, poetic and thought-provoking. The vivid imagery alludes to wars, suffering, injustice and pollution. Parts of the songs have been interpreted as referring to nuclear fallout, but according to a 1963 radio interview, when Dylan refers to “pellets of poison are flooding the waters” that is a metaphor which applies to the lies that are being propagated through the media. Sadly, the song continues to remain relevant.

A Change Is Gonna Come – Sam Cooke (1964)

“A Change Is Gonna Come,” is one of the most important songs ever written. Sam Cooke was inspired to compose this timeless civil rights standard after listening to the Bob Dylan’s 1963 protest classic, “Blowin’ In the Wind.” If a white man could eloquently articulate the struggles of black people, then surely someone who lives those struggles daily should be able to. Cooke tapped into his own personal experiences of dealing with racism and discrimination. He also went back to his gospel roots to record a deeply moving anthem of hope.

Eve of Destruction – Barry McGuire (1965)

This modern-day protest standard was written by 19-year-old P. F. Sloan. McGuire’s definitive version appears on his 1965 album of the same name. The tune is a somber warning of pending apocalypse.

It is not only anti-war, but it addresses several social issues including civil rights. One of the key lyrics is: “You’re old enough to kill, but not for votin’,” which refers to the fact that at the time the US voting age was 21, while the minimum draft age was 18. The voting age was lowered to 18 in 1971. That lyric resonates because the songwriter was unable to vote. The youth have always played important roles within protest movements.

Four Women – Nina Simone (1966)

Nina Simone is not only an influential vocalist, but she is also one of the most important artists in the history of socially conscious music. “Four Women” was penned by Simone and it appeared on her classic 1966 album, Wild Is The Wind.

The poignant tune is a character study of four black women. The lyrics provide insightful commentary on racial injustices and the longstanding effects of slavery.

The song once again took on renewed relevance when Jay-Z sampled it in his 2017 tune, “The Story of OJ.” Jay-Z effectively uses the sample as a musical canvas to explore similar themes.

Respect – Aretha Franklin (1967)

“Respect” is from Franklin’s 1967 breakthrough album I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. Originally written and recorded by Otis Redding, Franklin claimed ownership and transformed it into a timeless anthem of female empowerment. Franklin modified the song by adding the: “R-E-S-P-E-C-T / Find out what it means to me.” Franklin wasn’t asking for respect, she was demanding it.

Even when not singing direct protest songs. Franklin’s music possessed a social awareness. By her vocals alone, she could turn any tune into an empowering anthem.

Say It Loud: I’m Black and I’m Proud – James Brown (1968)

This black empowerment funk classic by the “Godfather of Soul” is one of the most direct and celebratory anthems in the history of protest songs. The call and response of the children chorus is equally infectious and potent.

Fortunate Son – Credence Clearwater Revival (1969)

CCR’s lead singer John Fogerty composed “Fortunate Son” as a scathing denouncement of elitism in connection with the Vietnam draft.

In a 1969 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Fogerty said the following about the song’s inspiration: “Julie Nixon was hanging around with David Eisenhower, and you just had the feeling that none of these people were going to be involved with the war. In 1969, the majority of the country thought morale was great among the troops, and like eighty percent of them were in favor of the war. But to some of us who were watching closely, we just knew we were headed for trouble.”

The song’s timeless message goes beyond being anti-war and it transcends the Vietnam era. It makes powerful statements about elitism that still apply. It is a rousing rally cry for the 99%.

Working Class Hero – John Lennon (1970)

John Lennon has played an important role in helping to write the cannon of protest songs. “Working Class Hero,” which appears on his 1970 album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, is Lennon at this most poignant. Some of his other tunes may be more well-known and direct, but they can also border on simplistic sloganeering.

“Working Class Hero” is an insightful commentary on class splits and how the system is designed to manipulate people into becoming cogs in the machine. It also examines the role that religion and media play in the indoctrination of the masses.

What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye (1971)

Marvin Gaye’s entire What’s Going On album contains multiple songs that could have been included. Gaye based the concept of his legendary album on the story of a soldier returning from the Vietnam war. Marvin had a personal connection to the story. His brother was a Vietnam veteran who now had to adjust to new realities.

The classic title track was co-written by Renaldo Benson (who was a member of The Four Tops). Benson’s motivation stemmed from disturbing news reports of the police brutality that was happening at student protests of the Vietnam war.

Instead of being an angry indictment, it is a mournful questioning. Sadly, it continues to resonate.

Freddie’s Dead (Theme From Super Fly) – Curtis Mayfield (1972)

“Freddie’s Dead” is from the soundtrack of the 1972 blaxploitation film Super Fly. Mayfield composed the entire soundtrack. In contrast with the film (which was criticized for glorying drug dealing), Mayfield provided insightful commentary on poverty and drugs and explores the systemic issues which contributed to these societal problems.

The funky tune deals with the tragic tale of Fat Freddie, who is forced to turn to crime to pay off his debt to his drug dealer. It would be easy to dismiss him as another junkie, but Mayfield chooses to acknowledge the humanity and tries to empathize with the circumstances which leads people down the wrong path.

Get Up, Stand Up – The Wailers (1973)

“Get Up Stand Up” is from The Wailers’ 1973 classic album, Burnin’ (this was their last album before becoming known as Bob Marley & The Wailers). It is a stirring rallying cry against oppression.

It’s important to acknowledge reggae’s considerable contribution to the global protest movement. In a sense, reggae is a form of Jamaican folk music and many of the best songs well articulate the human struggle for justice.

Bob Marley’s wide appeal allowed his songs of protest to be exported beyond Jamaica. Even if you don’t fully comprehend Marley’s political and religious ideology, the sentiments of an anthem like “Get Up Stand Up” are universal. Throughout the world there are oppressive forces that need to be stood up against.

The Bottle – Gil Scott-Heron (1974)

On “The Bottle,” influential jazz poet Scott-Heron not only addresses the dangers of alcoholism, but he examines the situations which lead people to turn to “the bottle” as a means of escaping personal demons and societal problems. Instead of being an indictment it is an empathetic warning message.

The Pill – Loretta Lynn (1975)

This then controversial ode to the birth control pill is a celebration of sexual liberation and women empowerment.

Lynn first recorded the tune in 1972 at a time when there was much religious and conservative opposition to the pill. Because of this her record company blocked her from releasing it, so the song wasn’t released until 1975. Many country radio stations banned the song. Even though it didn’t do as well on the Billboard country charts as her earlier singles, it did crossover, becoming her biggest hit on the US Billboard pop charts.

The song is still relevant considering the ongoing battles with women’s reproductive rights.

Zombie – Fela Kuti and Afrika 70 (1976)

This afrobeat classic is a 12-minute epic take down of the corrupt Nigerian government. The symbolic use of zombies was used to denounce the tactics of the Nigerian military.

Kuti’s music was considered so potent that he was considered an enemy of the state. This lead to a thousand soldiers attacking the Kalakuta Republic, the compound which housed Kuti’s family, band mates and recording studio. This attack resulted in the murder of his mother. In protest to the vicious attacks, Kuti had the coffin of his mother delivered to the main army barrack in Lagos. He addresses this in his 1981 composition “Coffin for Head of State.”

White Riot – The Clash (1977)

“White Riot” was The Clash’s first single and it helped establish the band has one of the most important bands in the history of socially conscious music.

The tune addressed the 1976 riots at Notting Hill Carnival, that band members Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon were both involved in. The riot was in response to the fact London’s Caribbean residents were victims to racist policing practices. It encourages those with more favorable circumstances to use their privilege to become an ally for the marginalized. The song is a strong rebuke against white passiveness.

(Sing If You’re) Glad to Be Gay- Tom Robinson Band (1978)

This empowering gay pride anthem also explores societal attitudes towards gay people. For example, it references British police raids that were taken place in gay pubs even after homosexuality was decriminalized in 1967. It is a stirring rally cry against discrimination.